Research

By altering weather patterns, resource availability, and landcover at historically rapid rates, human activity poses an unprecedented threat to biodiversity. While some populations appear relatively resilient to these impacts, others have proven to be extremely sensitive. If we hope to mitigate future biodiversity loss, there is an urgent need to identify which species are most threatened by human activity and to understand the reasons for their vulnerability. Unfortunately, gaps in our knowledge of natural history frequently prevent us from appreciating how human activity threatens species, hindering our ability to implement effective conservation strategies. My research program focuses on strengthening our understanding of natural history variation throughout the annual cycle to more accurately predict how populations will respond to ongoing threats.

While anthropogenic climate and landcover changes have sparked grave conservation concerns, they also present unprecedented opportunities for studying the processes that shape biodiversity. Describing how species distributions and interactions among species shift in response to contemporary environmental changes can illuminate the evolutionary history underlying current patterns of diversity, help us predict what future species assemblages will look like, and potentially identify strategies for mitigating biodiversity loss. To this end, I also study how human activity mediates hybridiziation between closely related lineages.

Describing threats to birds during molt

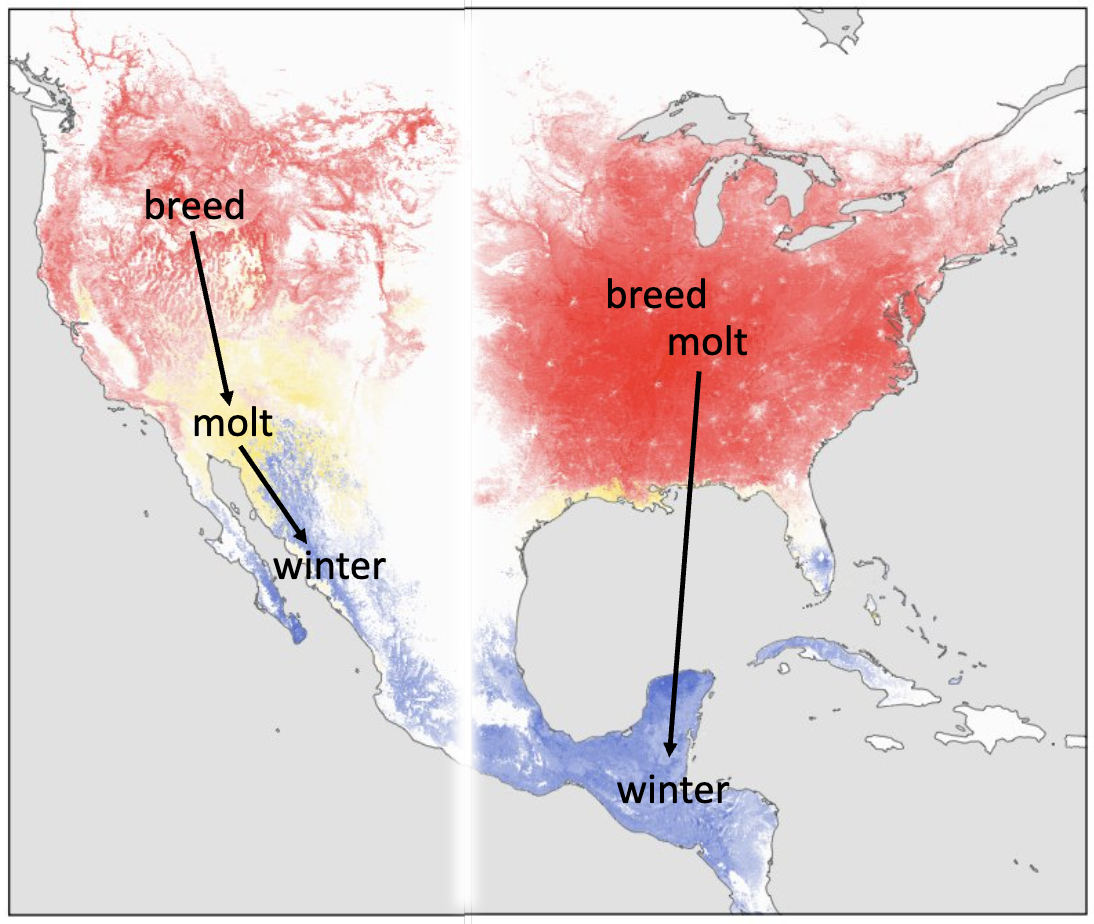

Molting, the process by which birds replace their feathers, is a necessary annual event with major ramifications for fitness. Birds rely on feathers for a wide variety of functions critical for survival and reproduction, including flight, communication, and thermoregulation. Because exposure to the sun, abrasive vegetation, and parasites wear feathers down over time, most birds molt body and flight feathers at least once per year to maintain sufficient feather function. Molting represents one of the most metabolically demanding events in the annual cycle, with the durability of new feathers directly proportional to the amount of time and resources that a bird allocates. Despite this link between conditions during molt and individual survival, molting remains far and away the least studied stage of the avian annual cycle. For one of my dissertation chapters at the University of Wyoming, I analyzed long-term community science and climate datasets to demonstrate associations between ongoing shifts in monsoon precipitation volume and phenology and population declines for many species that breed in western North America. We hypothesize that deviations from historical precipitation regimes increasingly deprive birds of sufficiently predictable resources to supply molt, elevating mortality rates. This study presented some of the first evidence that anthropogenic climate change negatively impacts bird populations during molt

Molting, the process by which birds replace their feathers, is a necessary annual event with major ramifications for fitness. Birds rely on feathers for a wide variety of functions critical for survival and reproduction, including flight, communication, and thermoregulation. Because exposure to the sun, abrasive vegetation, and parasites wear feathers down over time, most birds molt body and flight feathers at least once per year to maintain sufficient feather function. Molting represents one of the most metabolically demanding events in the annual cycle, with the durability of new feathers directly proportional to the amount of time and resources that a bird allocates. Despite this link between conditions during molt and individual survival, molting remains far and away the least studied stage of the avian annual cycle. For one of my dissertation chapters at the University of Wyoming, I analyzed long-term community science and climate datasets to demonstrate associations between ongoing shifts in monsoon precipitation volume and phenology and population declines for many species that breed in western North America. We hypothesize that deviations from historical precipitation regimes increasingly deprive birds of sufficiently predictable resources to supply molt, elevating mortality rates. This study presented some of the first evidence that anthropogenic climate change negatively impacts bird populations during molt

Now, as a National Science Foundation postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, I am diving deeper into the underlying physiological and genetic mechanisms that influence vulnerability to climate change during molt. My current research aims to describe where and when bird populations molt, the environmental cues that regulate molt, and the genetic variants underlying adaptive variation in molting strategies. This work has entailed deploying individual tracking devices on birds throughout western North America, exposing captive birds to different environmental treatments and describing their molt and migratory activity, and generating transcriptomic sequences from multiple tissues collected from molting birds. By developing a deeper understanding of molting location and phenology, as well as the extent to which individual birds can flexibly tune these phenotypes in response to environmental conditions, I hope to work with managers to develop appropriate strategies for buffering bird populations against ongoing environmental changes during this understudied yet critical period of the annual cycle.

Related Publications:

Dougherty, PJ, RS Terrill, and MD Carling. 2025. Molting strategy influences vulnerability to climate change in migratory birds. The American Naturalist. Link

A full annual cycle approach to studying speciation

As individual tracking devices and year-round genetic sampling become more accessible, research on the historically understudied nonbreeding period has exploded in the past decade. These studies are revealing tremendous inter- and intraspecific variation in migratory, molting, and other nonbreeding strategies, thereby informing efforts to protect bird populations throughout the entire annual cycle. However, we still have much to learn about where and when nonbreeding adaptive variation influences reproductive isolation and speciation. Nonbreeding phenotypes determine which individuals survive between breeding periods and the condition of these individuals at the start of breeding, and therefore inherently influence reproductive isolation. I am studying how adaptive variation in molt and migration strategies between recently diverged taxa mediate gene flow by influencing relative hybrid fitness. My previous work on captive birds demonstrated that some hybrids between taxa with different molt and migration phenology exhibit novel strategies, potentially attempting to replace flight feathers during migration. If these novel strategies force hybrids to molt at times or locations without sufficient resources, they may struggle to supply feather growth and suffer higher mortality rates.

Related Publications:

Dougherty, PJ and MD Carling. 2025. Incorporating the full annual cycle when studying reproductive isolation and speciation. Journal of Avian Biology, 2025(5): e03450. Link

Evolution and speciation in a changing world

Describing how hybrid zones respond to anthropogenic influence can illuminate how the environment regulates both species distributions and reproductive isolation between species. Unfortunately, only a few hybrid zones have been repeatedly sampled over long enough time frames for significant changes to be detectable. As part of my dissertation, I compared the genetic structure of an avian hybrid zone in the Great Plains of North America at different sampling periods. I observed a rapid westward shift in the center of the hybrid zone in recent decades. By integrating community science datasets, such as eBird, with climate data, I was able to attribute this shift to recent environmental changes and identify anthropogenic climate change as a key mediator of introgression in this system.

Related Publications:

Dougherty, PJ and MD Carling. 2024. Go west, young bunting: recent climate change drives rapid movement of a Great Plains hybrid zone. Evolution, 78(11): 1774–1789. Link

Minor, NR, PJ Dougherty, SA Taylor, and MD Carling. 2021. Estimating hybridization in the wild using community science data: a path forward. Evolution, 76(2): 362-372. Link