Research

Adaptive divergence in molting behavior as a mechanism of reproductive isolation in birds

The Great Plains of North America host a suture zone where multiple pairs of closely related plant and animal taxa hybridize. Most of the avian hybrid zones in the Great Plains are characterized by strong divergence in molt and migration phenology, with eastern taxa molting primarily before migrating each fall and western taxa molting during an extended migratory stopover in the Southwest. This stark difference in life history may manifest as disadvantageous phenotypic combinations in hybrid offspring, imposing strong post-zygotic reproductive isolation and maintaining the genetic integrity of parental taxa. I am currently integrating studies of captive birds, whole genomes, stable isotopes, and museum specimens to investigate how molt phenology divergence mediates introgression in these systems.

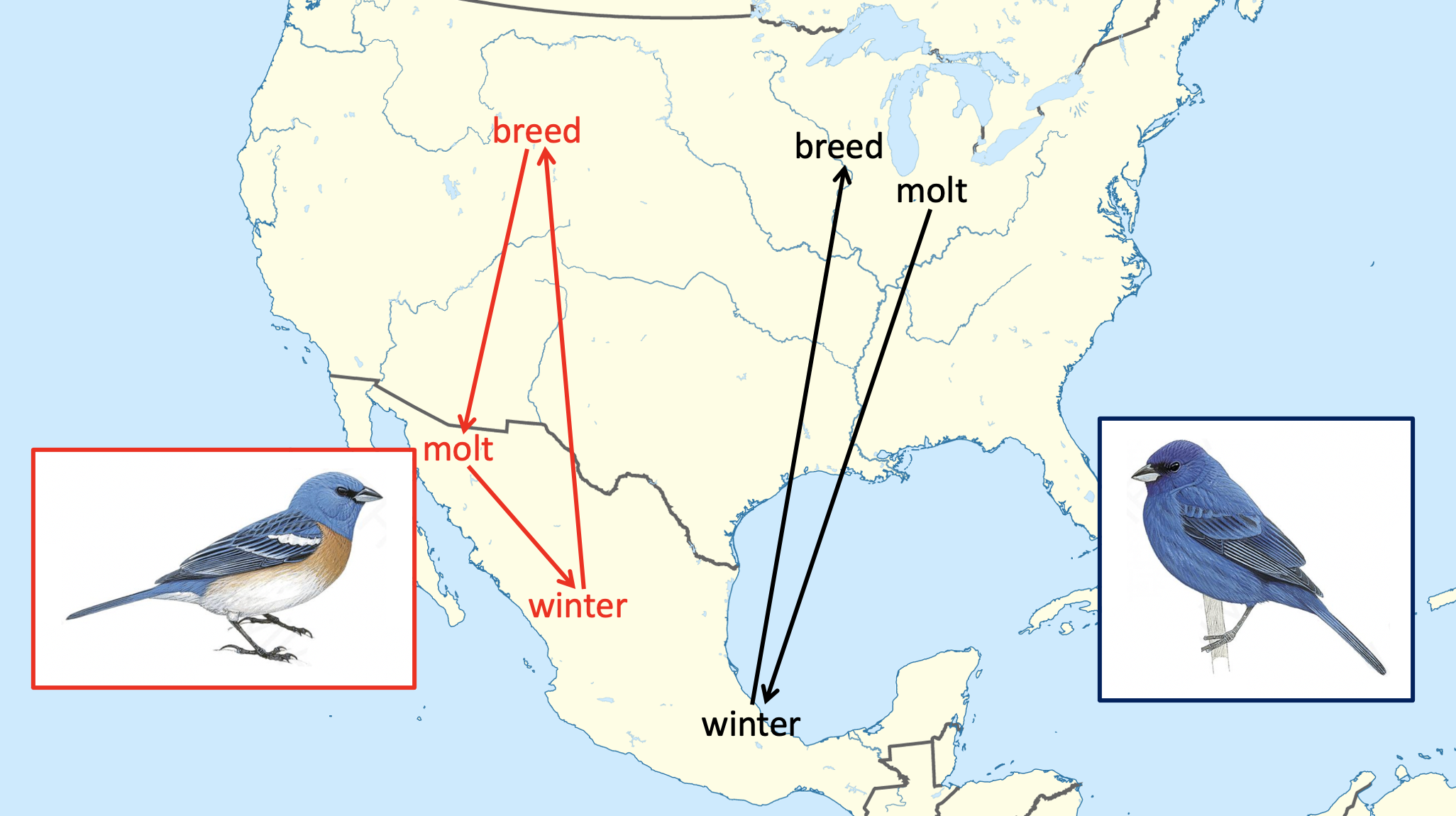

Relative breeding, molting, and overwintering locations of Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) and Lazuli Bunting (P. amoena), which hybridize where their breeding distributions overlap in the Great Plains.

Relative breeding, molting, and overwintering locations of Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) and Lazuli Bunting (P. amoena), which hybridize where their breeding distributions overlap in the Great Plains.

Western Molt-Migrant Conservation

By altering weather patterns, global temperatures, and precipitation regimes more rapidly than ever before in the history of life on earth, anthropogenic climate change poses an unprecedented threat to biodiversity. If we hope to mitigate future biodiversity loss, there is an urgent need to identify which species are most vulnerable to climate change and to understand the causes of their vulnerability. Unfortunately, gaps in our knowledge of natural history frequently prevent us from appreciating how climate change threatens species, hindering our ability to implement effective conservation strategies. I am investigating how molting behavior, a chronically understudied aspect of avian biology, can render bird populations vulnerable to climate change. If birds are unable to access sufficient resources at the time of year when they carry out molt, their risk of mortality increases. To meet this heightened metabolic demand, many species of migratory songbirds that breed in western North America have evolved to align their annual molt with a productivity boom induced by the North American monsoon. However, as climate change alters the timing and strength of the monsoon, individuals may now attempt to molt without sufficient resources and populations may start to decline.

By altering weather patterns, global temperatures, and precipitation regimes more rapidly than ever before in the history of life on earth, anthropogenic climate change poses an unprecedented threat to biodiversity. If we hope to mitigate future biodiversity loss, there is an urgent need to identify which species are most vulnerable to climate change and to understand the causes of their vulnerability. Unfortunately, gaps in our knowledge of natural history frequently prevent us from appreciating how climate change threatens species, hindering our ability to implement effective conservation strategies. I am investigating how molting behavior, a chronically understudied aspect of avian biology, can render bird populations vulnerable to climate change. If birds are unable to access sufficient resources at the time of year when they carry out molt, their risk of mortality increases. To meet this heightened metabolic demand, many species of migratory songbirds that breed in western North America have evolved to align their annual molt with a productivity boom induced by the North American monsoon. However, as climate change alters the timing and strength of the monsoon, individuals may now attempt to molt without sufficient resources and populations may start to decline.

Irruptive Fringillid movements

Perhaps no other animals epitomize the concept of facultative migration better than seed-eating birds that breed at high latitudes. When food supplies are sufficient year round, these species remain near their boreal and subarctic breeding areas throughout the winter. In years when seed crops fail however, entire populations may migrate hundreds of miles southward to winter in temperate latitudes. For my undergraduate honors thesis, I analyzed historic Christmas Bird Count and eBird records to explore spatiotemporal variation in the winter movements of high latitude breeding finch species. Together with Dr. Herb Wilson, we demonstrated that northern finches invade southward in relatively even numbers across latitudes. We also found that temperate-breeding finches tend to migrate southward in the same years as their northern counterparts.

Related Publications:

Dougherty, PJ, and WH Wilson Jr. 2018. Evidence for a relationship between the winter movements of the Common Redpoll (Acanthis flammea) and the American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis). The Open Ornithology Journal 11:1-26. Link

Dougherty, PJ. 2016. Spatial and temporal patterns in irruptive fringillid movements. (2016). Colby College Honors Theses. Link